Thinking Through Archives

Looking back at our first(!) year, and peering forward at what's to come

A belated happy 2022!

When we promised this was an infrequent newsletter, we meant it. This newsletter is a space for us to share what’s new, but also to expound on our burning questions and unresolved doubts: cloud projects are released into the world, but our project of criticality is never finished. We hope that you’ll write back with your thoughts too.

We printed our first book in May 2021, went through a third lockdown and a frenzied re-opening, and then - in quick succession - made an online exhibition and a physical one. Books printed, pictures hung, deadlines just met. Our time for thinking had to be temporarily set aside, caught in the unrelenting demands of production. Our ink had barely dried, paper wet to the touch.

Looking back now, one thing is clear. Time and again, the thread in these three projects was the archive.

The sign archive magnetizes desire, memory, splinters of self, grief, energy—fugitively, like iron filings. Its poetics, mobilized in art, facilitates jouissance. Its technologies of construction, toughened by change, produces the solidities we may choose to call identity; produces, in art, a politics of assemblage or pastiche or mosaic, depending on the period of making. Archive conjures the chimerical possibility of reconstitution. It also seduces with the possibility of reinvention.

[…]

Archives titillate out of sheer plenitude of hope secreted in their folds.

- Marion Pastor Roces, “Archive,” in Ctrl+P 19, p. 6.

More than a repository of material, the archive is delicious with the possibility of power and history. Scholars drool over material, egos hunger to be canonised, vacuums long to be filled. The twin towers of knowledge and remembrance loom large in a place where there is little coherence in our sense of the past: the project of history often becomes conflated with the project of grasping for authority.

We soundly reject this. cloud projects was incubated in Malaysia Design Archive, an independent archive of visual culture, where I (Sheau) worked as a Research Fellow and later Research Lead after graduating and moving back from the US. MDA was founded in response to the paucity of open access materials related to graphic history in Malaysia. Over ten years on, their archival efforts have tended to concentrate on materials that would fall outside the purview of state archives, questioning what is important, and to whom.

These same questions were at the heart of O For Other, a blog I ran with Yap Lay Sheng, Simon Soon etc. at MDA (and still sometimes update!). We blogged about objects, broadly defined, to “explore the ordinary, the imaginary and the fugitive.” We wrote, edited, and published stories about the lives of things, as they moved around in the world, as they interacted with the individuals around them, as they became portals to other times or places. I became fascinated with the possibility of not merely documenting or writing about object circulations, but also participating in their economy of moving around. It was there that our first book was thought.

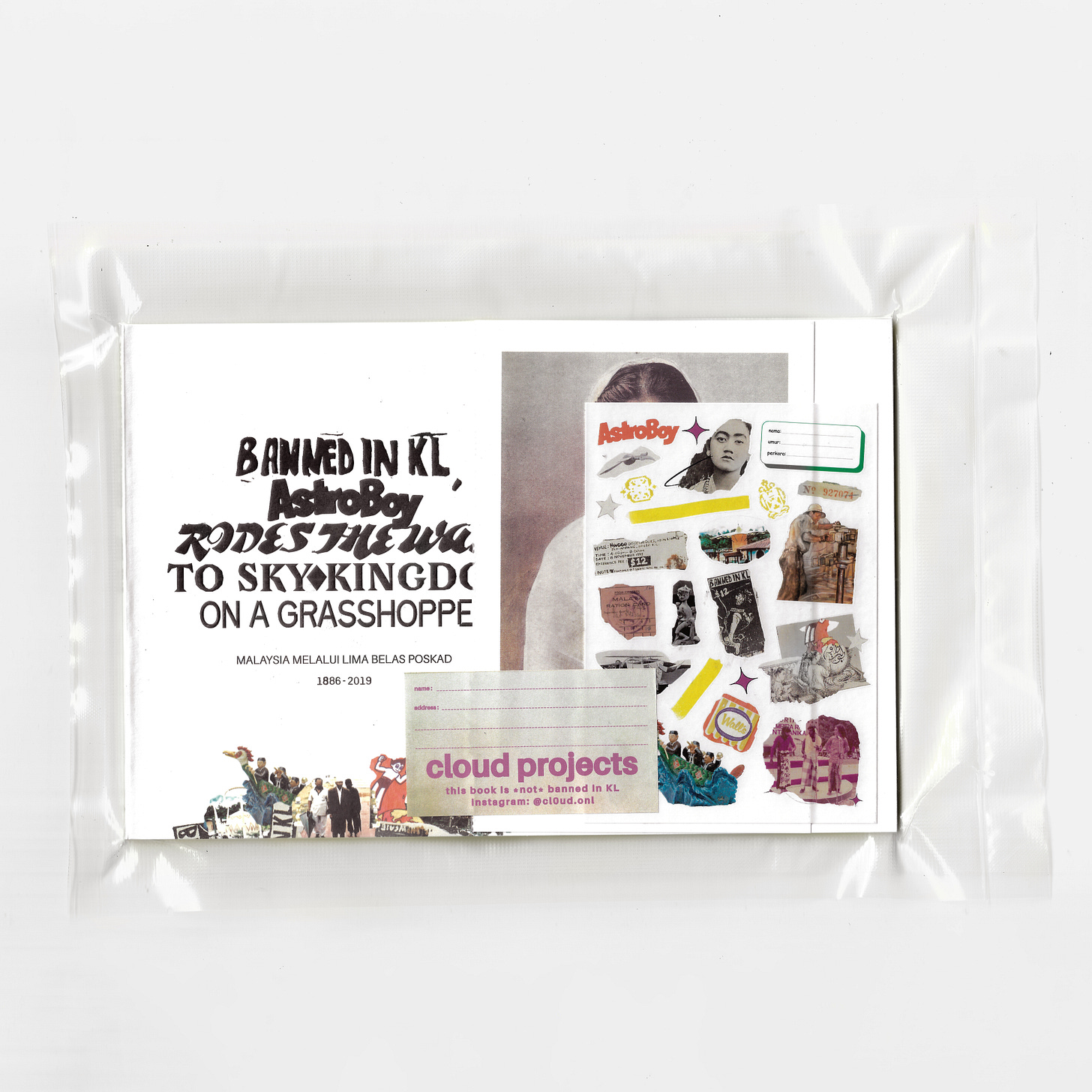

Translating Archives: Banned in KL

The book began with an impetus to translate some of the materials at MDA, and with that, give them the interpretive frames of contexts and questions. If you haven’t seen it, the book chronicles an image from each decade in a history of (or, more accurately, around) Malaysia, gives the reader a 300(ish)-word writeup in both BM and English, and then allows the postcard image to be freed from the page through a perforation. When you’re done tearing out all the postcards, the front and back covers can be folded in half and you’ve essentially lopped off the right half of the book. Although the material was mostly built off the MDA Core Collection, we also featured the works of artists (a Yee I-Lann tikar, a sculpture referencing MH17 by Hoo Fan Chon, a painting from Malaysians by Mohamed Hoessein Enas, a photograph of Sky Kingdom by Danny Lim), works from other archives and independent collections (such as The Ricecooker Archives), and works buried within the indices of larger collections.

If the national project was an exercise in imagination, what better way to affirm unity than to render its difference in the same brush? What better way to insist on wholeness than by the literal and metaphorical binding of pages onto the same spine?

This small book—and the archive from which the book primarily draws, Malaysia Design Archive—is, in many ways, as naive and artificial a project as Malaysians [by Mohamed Hoessein Enas]. However, unlike Malaysians, both the book and the archive do not aspire towards wholeness. There is no doubt that the history of a place cannot be told in fifteen images, nor can a single image ever represent a decade. If there is an attempt to capture an idea of diversity—of thought, of gender and of geography—we acknowledge that it will always be incomplete and insufficient. The nature of MDA’s archival mission is patchy: we collect, within our limited means, artefacts that spark something within us. The stories we tell (and common sense) come later. We live enthralled by objects.

- Preface to Banned in KL, Astro Boy Rides the Wave to Sky Kingdom on A Grasshopper

Some artifices concerning Banned in KL:

the nation

the archive

the collection

the postcard collection

the book of postcard collections

the history book

the decade

history

the fragment, the whole

the retrospective

the book itself

Banned in KL is a book, but it is also a collection of postcards, a chronicling of MDA’s collection, a history of Malaysia, and whole that has wholes. Maybe it is the postmodern moment, but it felt strange to make a book that contains just text. I like to imagine postcards torn out and sent around, these rough 230gsm papers floating in the mail.

Eventually, the translation itself gained a life of its own.

Contending with Archives: wawasan.directory

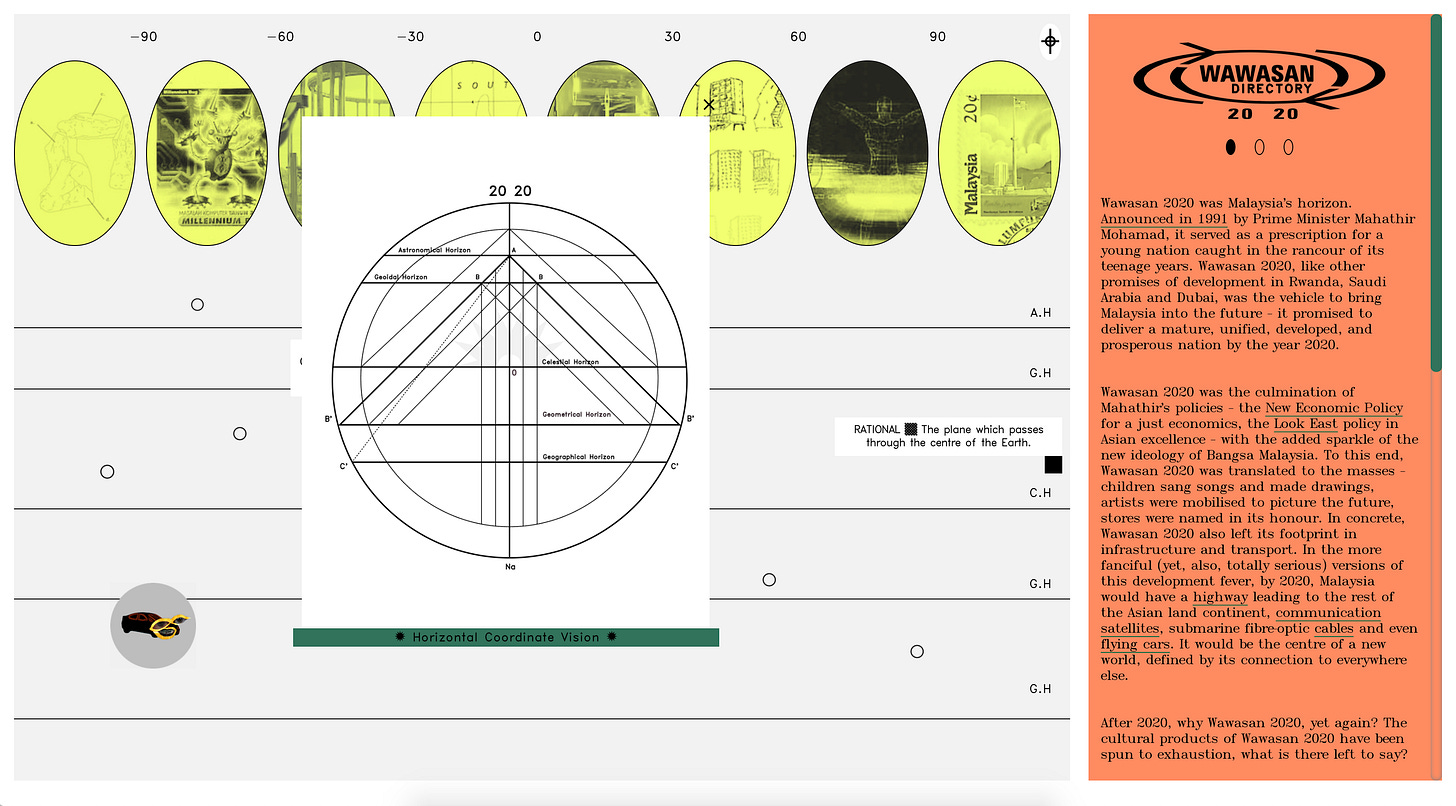

Simultaneous with our work of translating archives was also that of building one. In the pre-pandemic cultural moment that was the beginning of 2020, Lay Sheng and I made a series of ugly slides for O For Other parodying a 1994 issue of Men’s Review, which itself was a parody of Wawasan 2020, the futuristic vision declared by Mahathir Mohamed in 1991. Denise, who was writing a thesis on Wawasan 2020’s visual history, got in touch with MDA to build a Wawasan 2020 collection funded by the Design History Society.

Visits to Amcorp mall, e-Bay buys, speaking to others who have worked on Wawasan, and many hours trawling the internet later, we came to realise that our archive would always be incomplete. It was a question not merely of what copyright allowed us to include, but also what we could access.

Much like Banned in KL, wawasan.directory does not see the archive as a repository of truth. We realised that archival bureaucracy would, in fact, obfuscate the affect at the heart of Wawasan 2020. Rather than seeing it merely as a futuristic program, with its rhetoric and performance - the speeches, the forward motion, the parades - it mapped a structure of feeling. Instead of trying to collect materials containing these feelings, we then began to ask ourselves how we could capture the gap between us, a generation that grew up with The Vision, and us then, in the visioning. In other words, the question became: how do we speculate out of the archive?

Let us instead consider Wawasan 2020 as representation. Wawasan 2020 is – to borrow the phrase from architectural historian Reinhold Martin – a cipher, “encod[ing] a virtual universe of production and consumption, as well as a material unit, a piece of the universe that helps to keep it going.” It both is, and represents, the new. It matters insofar as it is able to stand in for a bevvy of contradictory ideas in the hopes of capturing significance, including the adjective word-soup of its description, the leftist ideals, the neo-liberal realities. The Vision is both the vehicle and its movement, but also, it doesn’t really matter.

- Curatorial Statement, wawasan.directory

Mining the Internet for All the Lands Within the Seas

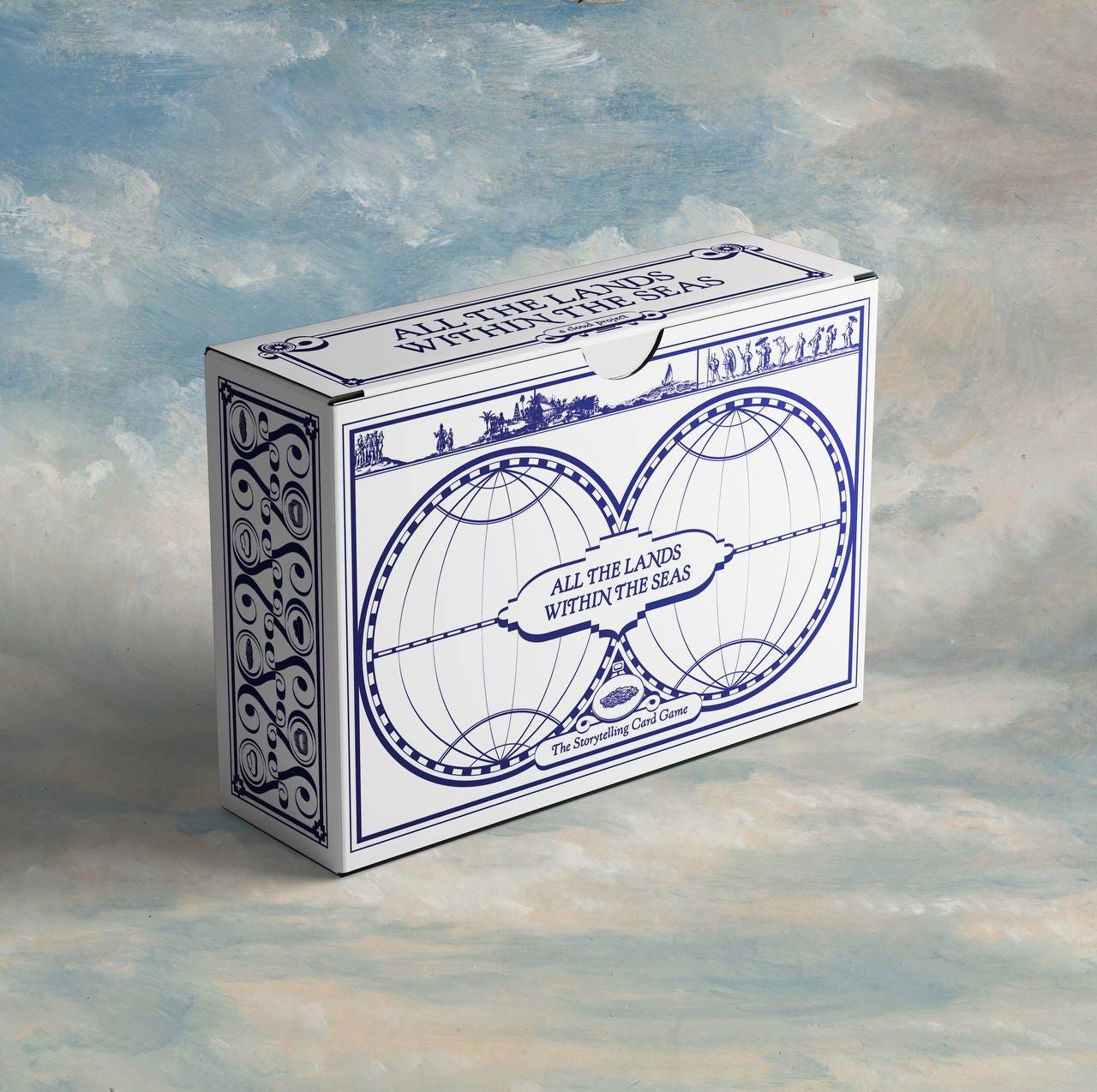

If wawasan.directory was a chance for us to think about building archives, and correspondingly, its limits, then All the Lands Within the Seas was a chance for us to trawl colonial archives and identify their gaps. Our work is in pursuit of epistemic justice: whether that is in making PDFs of our projects freely available online, making sure our work is copy-left under Creative Commons, or in insisting on anti-hegemonic work.

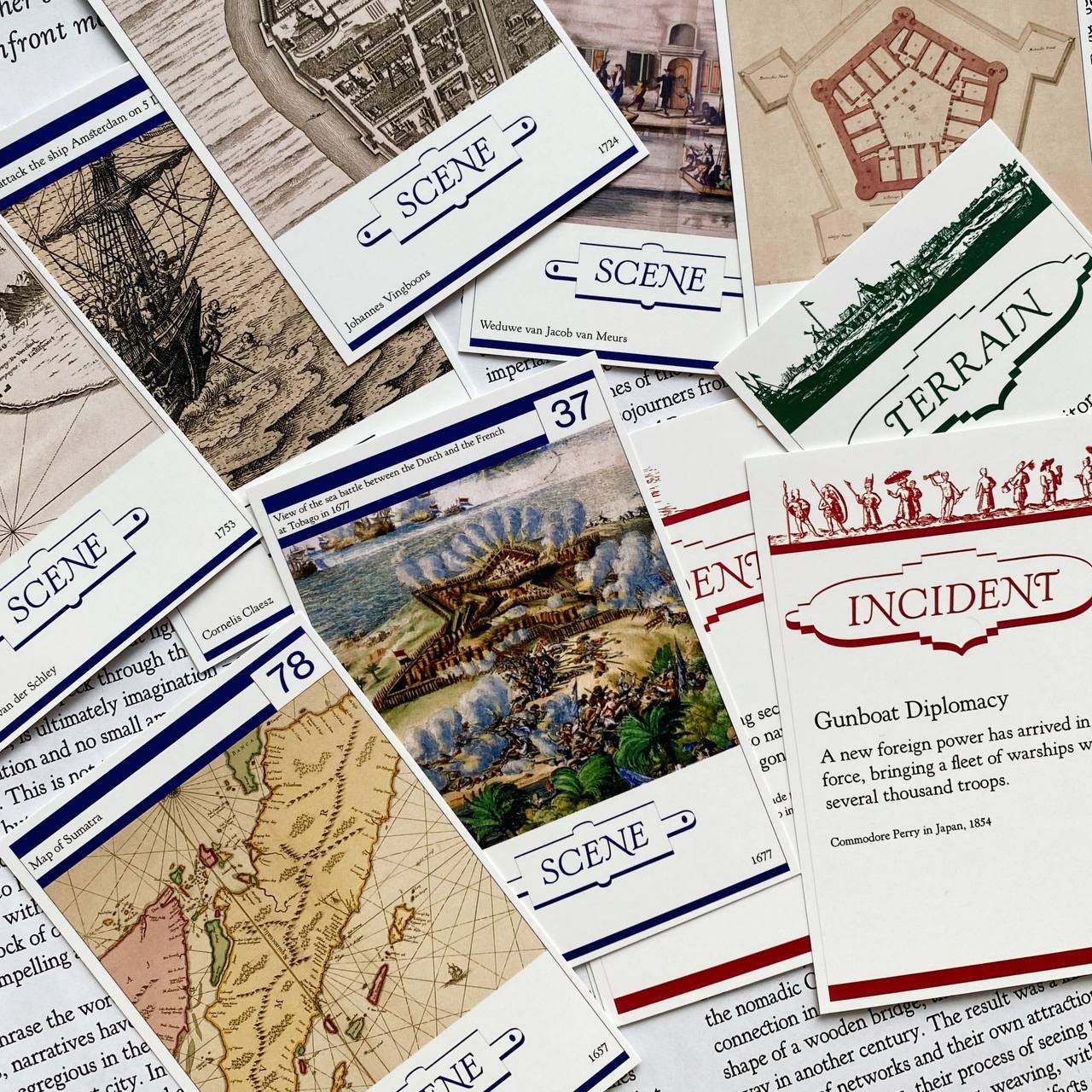

So what would it mean to take Melaka, the place upon which Semenanjung ethno-nationalists build their fantasies, and make an exhibition of its visual history in the distinctly small, low-key space of The Back Room in The Zhongshan Building? What started as a simple exhibition of original maps and prints from the 16th to the 19th-centuries, sourced from private collections, quickly became a chance for us to think about the contentious shadow of Melaka.

When grappling with the history of Melaka, we too must grapple with absence. Oftentimes, to fill the void, there is a great temptation to view Melaka as a centre of gravity, to lionise its legacy, and to then render the rest of the world as celestial bodies orbiting this sun of a port city. After all, Melaka has been inserted into our national narrative as the cornerstone of Malaysian identity. It is a legacy laden with baggage as a site of deep contestation and emotional import, for Melaka must carry all the weight of the pre-colonial Malaysian story: Melaka must be both Malay and “multicultural”, it must illustrate the “social contract” between the races and it must also trace the moral arc of Malaysia. In short, Melaka must be the righteous parable and raison d'être of the contemporary nation-state — this is its burden, and, thus, also its power.

- Curatorial Statement, All the Lands Within the Seas

Finding an image history of Melaka took us to archives outside Malaysia, namely Atlas of Mutual Heritage, Gallica, and Wikimedia Commons (whose knowledge politics of public access we are grateful for - yay to more archives making items freely available!). Alongside “original” prints, which themselves were made in multiple editions, the line between the reproduction and the real began to blur. What difference was there in a copy made in the 17th-century, and the 21st? In this vein, four works, also prints, were made for the show: three woodcut prints by Bam Hizal, and a collage by Amanda Gayle.

Yet in looking at images, and secondarily, primary texts that permeate our brochure, it becomes clear that there are glaring absences in the histories we are accounting for, ones that require exercises of further reading and close looking. This was what in part inspired the funky cropping exercise that was our card game, which invites players to tell stories, however grounded in fiction or reality. Instead of 1-1 reproductions onto cards, we took sections of images from our exhibition: perhaps an unseen figure in the corner, or a geography previously unnoted.

In this spirit, we also held events to rectify some of the biases in these luscious images. The Orang Laut, whose presence in colonial images often cursory, was the subject of a talk by Professor Leonard Andaya. The everything else of Melaka - that is, the invisible infrastructures that made its status as a port city possible - was the subject of another talk by Professor ShawnaKim Lowey-Ball.

But what of the slaves and indentured workers that made much of the city possible? And the women, whose invisible work often never made it into text or image?

The archive is, in this case, a death sentence, a tomb, a display of the violated body, an inventory of property, a medical treatise on gonorrhea, a few lines about a whore’s life, an asterisk in the grand narrative of history. Given this, “it is doubtless impossible to ever grasp [these lives] again in themselves, as they might have been ‘in a free state.’”

- Saidiya Hartman, “Venus in Two Acts”

After the Archive

The archive is slippery. The more we step away from it, the more we stand in relation to it. I have sometimes felt that to work in relation to the archive is not unlike to work in relation to the centrifugal gravity of other centers that assert themselves in knowledge (such as the nation-state), where we become “like… a wasp which sinks into the jam and drowns in it.” (Sartre)

I can’t help but think that this was the year of shaking off the yoke of doing the work of history in Malaysia: we had to deal with its towering shadows (Melaka, Wawasan 2020 - we’re just missing 1963 and May 13). These are young projects, born out of frustration, working through our angst, but with an irreverence I hope we don’t lose.

But what new expansiveness can emerge when we step away from the archive, or consider it secondarily? What if we started from drawings and graphics rather than starting from words and history? What stories can we spin from images? What happens when we move our practice from the realm of the reactive to the productive? What discursive frames do we operate in and how do we break them? In other words, what happens when we relegate the archive to the backseat?

These are our questions for 2022.

Much love,

Sheau

on behalf of team cloud (Amanda, KJ, Sheau)